The Great American, Grass Roots, Rockin’ Road Warrior Dream

The Great American, Grass Roots, Rockin’ Road Warrior Dream

by Bobby Rock

Here’s another excerpt from my upcoming book, which is a follow-up to The Boy Is Gonna Rock:

Will Drum For Food:

Surviving the Nineties with Clubs, Campgrounds, Clinics, and Credit Cards

This memoir focuses on the Nelson hey-day, on through a decade-plus of my pursuits as a drumming educator and solo artist. It delves deep into the creative, philosophical, and business aspects of surviving and thriving in both of those very different musical/cultural worlds and, as you might imagine, there are plenty of stories to tell! Here is an excerpt about my earliest motivations for pursuing the drummer-as-bandleader direction.

And again, this is an unedited, first-draft preview. Enjoy…

+ + + + + + + + +

The Great American, Grass Roots, Rockin’ Road Warrior Dream

I always had a fascination with that typical storyline of how most bands progress from A to Z in their “journey to the top.” They start off with nothing but some shit gear, a beat-up van or station wagon, and a few bogus gigs, where the five patrons in the bar barely notice them. And then the grassroots climb begins, as our heroes navigate a myriad of treacherous circumstances: roadside breakdowns, borderline financial ruin, perhaps a member change, maybe some drug or alcohol setbacks, and several epic stories of near-disaster that they barely survived.

But then, things gradually begin to pick up. The band’s live performances improve and they start writing better songs. More people start turning up to shows. Gear and transport are gradually upgraded and overall conditions improve ever so slightly. This all leads to more packed houses and even a few national act support spots where the band goes over well… which then leads to bigger and better gigs… which then leads to a bit more money and opportunity. And so the trajectory continues, until at last—after many close calls, disappointments, flame-outs, and then one, two, three or more false starts—a record deal is finally inked and the band steps up to the next level.

From there, the grind continues to various degrees, with some bands crushing it on their debut attempt (like Van Halen or GNR), and others needing a few records to hit their stride (like Kiss or Rush). Either way, this general narrative exists with practically every single band you can think of. Sure, there are anomalies, especially in our current “American Idol” culture of zero-to-sixty reality TV exposure and overnight YouTube sensationalism. But this classic narrative of the slow and steady grind had always appealed to me. Grassroots. No shortcuts. Building a die-hard following. Earning your acclaim. And, of course, engaging a journey of inexplicable struggle and strife—the likes of which most “mere mortals” could not (or would not choose to) survive—in a modern-day version of the classic Joseph Campbell Heroes Journey paradigm. You face the adversities, slay the dragons, and eventually, in your darkest hour, win the kingdom.

The only thing was, by 1990, I had never experienced the full arc of such a journey. I had become intimately acquainted with the agonizing first stages of the process, but not so much with the fruits-of-the-labor pay-off stages. And my first major gig, Vinnie Vincent Invasion, had already been primed in the sizable aura of the Kiss brand—at least in terms of elevating Vinnie to a stature of international notoriety right out of the gate. The same could be said of the Nelson gig. In addition to any cache the brothers may have inherited from their family legacy, they had already busted balls through many years of writing, gigging, and all the rest of it—long before I came along—to get to a record deal level.

And so, since leaving the Berklee College of Music and beginning to pursue that solo direction, I had developed somewhat of a romanticized version of what my own grass roots journey to the kingdom might entail. It would be a drummer-led situation (which was unusual, I know). Buddy Rich was the gold standard where drummers as bandleaders were concerned, but Billy Cobham had also had a great run fronting his various powerhouse ensembles. I was looking to combine some of Buddy and Billy’s “drum hero” attributes with a more rock-oriented, power trio vibe that was squarely inspired by guitar great, Eric Johnson.

Buddy, Billy… and Bobby!

(I literally just noticed the name-similarities in this moment:

5-letter names that begin with a “B” and end with a “Y”... which is followed by matching

consonants. Destiny, indeed! Now, if only I could

play like these motherfuckers!)

To that end, Eric was probably my biggest role model in this capacity: Virtuoso band-leader, fronting a classic power trio, and packing out clubs everywhere. Of course, this guy was a fucking monster without parallel who had procured legendary status throughout Texas for well over a decade before he would have his breakthrough record with "Cliffs of Dover” in 1990. Shit, I remember watching this guy burn the house down at venues like Cullen auditorium, with his first band, the Electromagnets, opening for the likes of prog rockers UK. But then later, at Rockefellers in Houston—one of my favorite all-time concert venues—I saw some Eric Johnson performances that have stayed with me to this very day. Man, could this guy wail... and did he ever play the long-game.

I remember having many conversations about this ideal with my childhood friend, Cobo. He was a huge believer in me, and in this concept of a grassroots ethos, having been a singer/songwriter in several popular Houston-area bands in the late 70s. And he was always the first to encourage me to put on the blinders and diligently head in that direction, without the distraction of all of these “dime-a-dozen” rock gigs. I think he saw the practical value of me doing them, but he was always that friend in the shadows, quietly whispering in my ear about the bigger picture aspiration. Do your own thing was his mantra. These talks always resonated with me and would help to fuel an ever-expanding vision that was developing in my mind:

My elusive power trio and I would go out and struggle in clubs, slowly and steadily building a rabid following around brilliant performances that featured stellar ensemble playing, deep, funky grooves with an arena rock edge, and, of course, solos… lots of solos… from everyone… steeped in that old school jazz world directive of spontaneous improvisation, and of no two shows, or solos, ever being the same. Obviously, I knew this kind of project would not be lighting the Billboard charts aflame, selling a ton of records, or reaching the same type of pinnacle that most standard-issue rock or pop bands might aspire to. But I was convinced that such a project could find its place in the world and blaze an interesting, innovative, and self-sustaining path in the landscape. And more importantly, I felt destined to manifest such a vision, even though I had no idea how to do it.

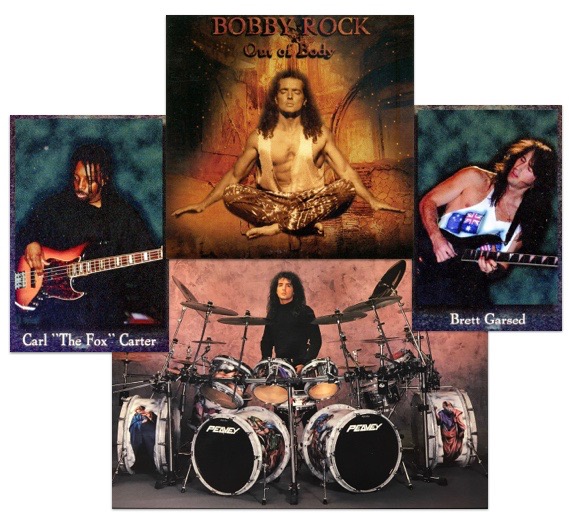

Good news was, I certainly had the band to pull this off. Bad news was, how does one begin? Brett (Garsed) was in LA at the time, waiting around for the initial crush of Nelson activities to kick in, but the Fox (Carl Carter) was clear across the country in Connecticut. We couldn’t just start playing around LA or the immediate region like a local band. No, our thing would have to be built around shorter jaunts of concentrated touring, where we would step into something of a national grind, as we would block out a few weeks or even a few months of calendar time and dive in. And then from there, we would wash, rinse, and repeat this grind six months or so later, in hopes that there would be a few more folks turning up the next time, and so on. But how could we get this thing going with the geographical realities at hand?

Also, let’s not forget about the harrowing financial logistics of touring on any level. We would need some kind of van to travel in, and that van would likely have to pull some kind of trailer with all of our gear. Then, in addition to us three band guys, we would need at least one crew guy—like my tech, Cubby—to deal with drums and backline, and most certainly a second guy to assist with set-ups and help drive while the rest of us slept… particularly if there were a lot of 500-plus mile hauls between back-to-back shows, which I was sure there would have to be. Now, figure modest wages and per diems (daily cash for food and other basics), a couple shitty motel rooms, fuel, van maintenance, and trailer rental, and all of a sudden, you have a pretty daunting set of numbers to account for—especially for a new, unproven project that was led by a drummer! It just felt like a pipe dream riddle with no real answer.

Oh, what a grueling yet joyous road we would travel...

Additionally, we had scheduling issues to navigate. The Nelson thing would be launching full-time soon and who knew how long Brett and I would be immersed in that. And the Fox was an in-demand east coast player, constantly juggling studio and live dates. It didn’t look too promising.

And yet, I literally felt like it was divinely ordained that the three of us make a run of it and take this thing to the stage and to the studio. It was just too unique, too compelling, and too exciting of an endeavor to not materialize beyond a mere vision. Somehow, I needed to figure this thing out… and fast.